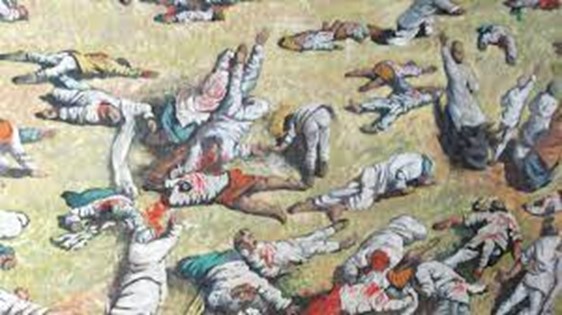

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre on 13th April 1919 was an inhumane act of the British Government’s colonial rule through the barbaric mass murder in cold blood against hundreds of innocent Indians (some put the figure at over 1,000).

The exact number of people killed, including women, children and at least one baby, is not known as General Reginald Dyer, responsible for the massacre, did not deign to count the corpses or the wounded left to die of their wounds overnight, some in a well where they had jumped to try and escape the bullets.

The background to the 13th April 1919 massacre

During the 18th and 19th centuries the British Crown had taken over more and more power in India from the corrupt, rapacious, militarised East India Company that had been increasingly plundering India since the end of the 16th century. This process was completed in 1859 by Queen Victoria, following the Company’s savage reprisals after the Indian Uprising of 1857.

The Rowlatt Act

During the 1st World War, the Defence of India Act was introduced in 1915, giving the British government extraordinary powers against Indian nationalists, including locking up people without trial and restricting speech, writing and movement. At the end of the war, on 18th March 1919, less than a month before the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, the Government introduced the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act, known as the ‘Rowlatt Act’, which extended its wartime emergency powers into peacetime in an attempt to consolidate India as ‘an integral part of the British Empire’.

However, in March 1919, following India’s huge contribution in soldiers and money for Britain’s World War I war effort, Indians expected the emergency measures to be eased and India to be given more political freedom, which to some extent was a recommendation in the Montagu-Chelmsford Report, presented to Parliament in 1918. But it was the Rowlatt Act that was introduced, not political reform nor the easing of emergency powers.

Gandhi’s call for a national strike

The Acts were met by widespread anger and protests in India, including in Punjab. Gandhi called for a national general strike – a ‘hartal’, a day of fasting, prayer, and abstention from physical labour. The response was overwhelming. On 6th April 1919, millions of Indians did not work, and for twenty-four hours India ground to a halt. As Gandhi travelled around the country, the British arrested him, provoking angry street protests

In Amritsar, in Punjab, the British authorities had expelled Nationalists, including Dr Saifuddin Kitchlow and Dr Satya Pal, triggering protests in the streets. On 10th April 1919, unarmed protesters were fired on, further protests were triggered resulting in attacks on some Europeans, looting, and burning of buildings.

The day of the massacre

On 13th April, following several days without protests, at least 10,000 people including women and children, went to or passed by the Bagh in the centre of Amritsar to observe Baisakhi (a religious festival for Hindus and Sikhs), attend a fair, or protest against the Rowlatt Act, the deportation of some of the Nationalist leaders, and the soldiers firing on the crowd a few days earlier. That morning Dyer went through Amritsar proclaiming that public meetings were banned. Either unaware of Dyer’s ban or in defiance of it or for a combination of the two reasons, people gathered in the Bagh.

Unable to enter the Bhag with his armoured cars and machine guns, Dyer arranged his several dozen troops at a raised strategic point just inside the main entrance and, without warning, ordered his soldiers to open fire on the unarmed people who were penned in with only the main entrance / exit to escape through. The soldiers continued until they only had enough ammunition left to retreat safely. In his report, Dyer callously stated, “I have heard that between 200 and 300 of the crowd were killed.”

The immediate aftermath

In India

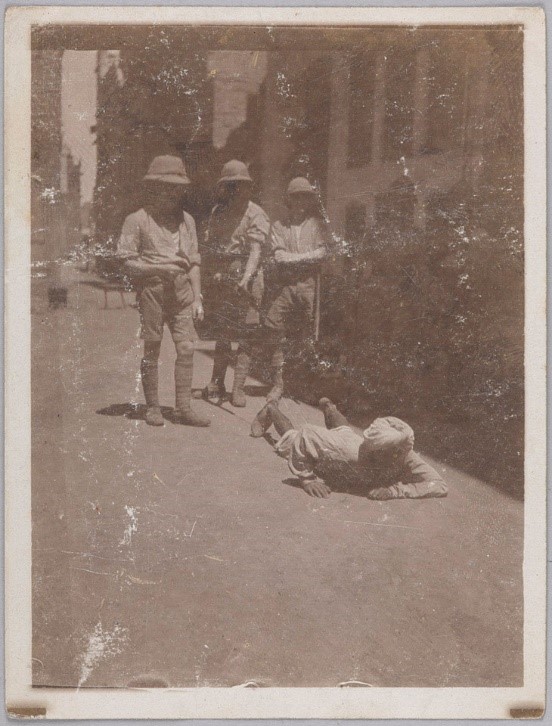

Brigadier-General Reginald E.H. Dyer instituted public whippings for Indians who approached British policemen and introduced ‘crawling’ for Indians using a street where a female European had been attacked, along with many other humiliations.

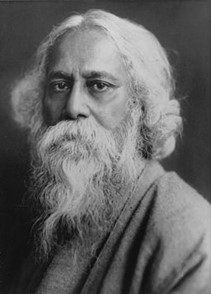

- Bengali poet, Tagore Rabindranath, the first non-European to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature (1913), renounced the knighthood that he had received in 1915, writing:

‘the time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation, and I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen, who, for their so-called insignificance, are liable to suffer degradation not fit for human beings’.

Mahatma Gandhi began organising his first large-scale and sustained civil disobedience satyagraha (truth and insistence) campaign (1920 – 22).

In Britain

Reaction to the massacre was mixed. Many praised Dyer’s actions, including the House of Lords, which gave him a jeweled sword inscribed with “Saviour of the Punjab.” In addition, over £1,000,000 in today’s money was raised by Dyer’s sympathisers and presented to him.

In 1920, in the House of Commons debate (recorded in Hansard), Winston Churchill (the Secretary of War) and Herbert Asquith, (former Prime Minister 1908 to 1916) were among MPs who condemned Dyer.

Churchill commented:

“one tremendous fact stands out – the slaughter of nearly 400 persons and the wounding of probably three or four times as many, at the Jallian Wallah Bagh on 13th April.

At Amritsar the crowd was neither armed nor attacking. I carefully said that when I used the word “armed” I meant armed with lethal weapons, or with firearms. “I was confronted,” says General Dyer, “by a revolutionary army.” What is the chief characteristic of an army? Surely it is that it is armed. This crowd was unarmed.

Pinned up in a narrow place considerably smaller than Trafalgar Square, with hardly any exits, and packed together so that one bullet would drive through three or four bodies, the people ran madly this way and the other. When the fire was directed upon the centre, they ran to the sides. The fire was then directed upon the sides. Many threw themselves down on the ground, and the fire was then directed on the ground. This was continued for 8 or 10 minutes, and it stopped only when the ammunition had reached the point of exhaustion.”

And former Prime Minister Asquith added:

“During the three days which elapsed from the 10th to the 13th of April there had been no outbreak. ………… the riots were put down on the 10th. The 11th and 12th passed in perfect tranquillity, or, at any rate, there was no further offensive.There is no evidence, nor could there be, that the bulk of the people were aware of the proclamation which had been issued earlier in the day. General Dyer with his troops, giving no warning of any sort or kind, fires indiscriminately into this mass of people until he has practically exhausted the whole of his available ammunition.“

In his own testimony at the government inquiry, Dyer had stated “I think it quite possible that I could have dispersed them even without firing.”

The Hansard record of the debate on the massacre provides insights into British colonial thinking at the time.

In the end, Dyer was forced to resign from the army but was not court-martialled.

Longer term

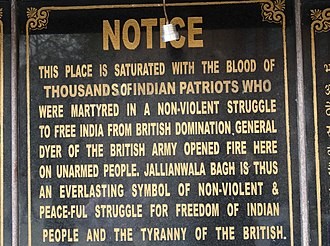

The Indian people’s relentless struggle continued with many sacrifices until India gained its independence in 1947. Since then the Jallianwala Bagh site in Amritsar has become a national monument.

Regret but no justice or reparations

Former PM Theresa May in 2019 said, ‘We deeply regret what happened and the suffering caused’. As yet no British Government has issued a full apology. Member of the House of Lords, Lord Sheikh has led the call upon this Government to issue a belated apology.

Aratrust considers this massacre was one of the defining events in Indian-British colonial history. Indeed, it is one of many inhumane British colonial atrocities whose legacies continue to shape Britain today. This atrocity remains part of the untaught history of the British Empire. Aratrust encourages reflection on these injustices, that an apology is given and that young people are educated to ensure that this history is not forgotten so that there is learning, allyship and peace.