Poem: India’s post-WW1 ‘expectations dashed and shackled by iron-hearted measures’.

Author’s Note

Following India’s great service to Britain during the First World War, there was an expectation that such a sacrifice would be rewarded with greater self-determination and even dominion status.

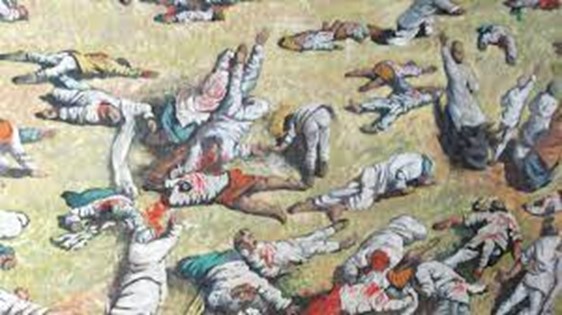

Regretfully, this was not to be. Instead those expectations were dashed by an iron repression exemplified by the massacre at Amritsar.

As for myself, I find it sad that today’s society appears just as ridden by dissension so increasingly I find my poems try to seek a bridge over the divides. In the case of this present poem, I hope the reader will note how I have tried to get inside General Dyer’s head in order to try to understand his extreme reaction but also how the poem moves from the red of the sun’s heat and people’s rage to the verdant green of the memorial garden, for it is only in the rosemary of remembrance and knowledge that we can collectively begin the climb to reconciliation and wisdom.

Murder in the Bagh (Amritsar, April 13th 1919)

In downtown Amritsar

years ago as now

there’s a stretch of walled off

ground, a bagh or garden even

where soldiers came with bullets

to cut, dig and plough.

General Dyer was commanding;

born under India’s grilling sun,

his upright back, iron grey hair

and brick red face

freely professing his services,

the years of duty done.

For this was British India

where few held the many in thrall,

the air heavy with rumour,

plots, sabotage, uprisings

and fiery freedom fighters

itching to heed the call,

for what was India to do,

having served the Raj with

loyalty, troops and treasure

in the bloody First World War,

finding herself now shackled

by iron hearted measures.

Indeed fevered lootings had

broken out only days before,

with five Europeans killed,

a bank trashed and a Miss

Sherwood thrown from her bike.

The General prescribed martial law.

Hours later the sun

was now a brand, a molten blot,

the air tinder dry. Had anyone

dared to stare it in the face

they might well have seen

an augurer, his eye blood shot.

When the General heard

of a gathering expressly banned

in the Bagh, enraged, he ordered

his fifty rifles March! Fire!

no warning given. Men,

women, children shot out of hand.

I had to teach a moral lesson,

in the aftermath the general said,

by barring all the exits,

directing fire where the crowd

was thickest, my bullet

points marked on the hundreds dead.

He was coming from a place

dark, steeply inclined,

known for its tunnel vision

which gives a tendency

to fixate and demonise

those your fellow kind.

Incensed by that lady’s

fallen honour, he salved her hurt

by making native passers-by

do penance at the scene

by crawling on all fours

down the walkway’s abject dirt.

When, General, you sped to the Bagh

with Lee Enfield in tow,

saying you were intent

to save the Raj by nipping

another Mutiny in the bud,

the reality was less than so

for while the Lords and others

were happy to defend

and bestow a handsome sum,

the Commons demanded

retirement to England

that career at an end.

Today, were you to stand

with an informed eye

in the Bagh by the entrance

where the soldiers stood,

you would be at a crime scene

inclined maybe to ask Why?

and What possible good

could crop in a garden

watered by innocent blood?

Then moving on, note

the pock-marked walls

where the bullets flailed,

the imposing memorial column,

the soldiers in topiary

caught in the rays,

rifles outstretched,

barrels ablaze

amidst the boxtree hedging;

trees and lawns,

enshrining a memory,

deep-rooted, ever green.

Wayne Carr

12th April 2021

Lord Sheikh’s letter to the PM requesting an official apology

The following letter from Lord Sheikh has been forwarded by the Indian Workers Association (GB).

Letter from Members of House of Lords and House of Commons

8th March 2021

The Rt Honourable Boris Johnson MP

Prime Minister

Number 10 Downing Street

SW1A 2AA

Dear Prime Minister,

We the undersigned members of House of Lords and House of Commons would like to write to you regarding the Jallianwala Bagh massacre which occurred on 13th April 1919.

On that day Indians of all ages and religions, which included Muslims, Hindus, Christians and Sikhs, gathered at the Jallianwala Bagh to celebrate the festival of Baisakhi and also peacefully protest at the arrest of two national leaders.

Acting Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer ordered his soldiers to block the main entrance of the garden and they opened fire on the unarmed civilians without warning. The firing was also directed towards the narrow open gates through which people were trying to escape. Winston Churchill referred to these events as “monstrous”.

It has been reported that 1650 rounds were fired and the official figures state 379 died, 1200 were wounded of whom 192 were seriously wounded. The exact numbers will never be known, and figures estimated by the Indian National Congress were higher than these.

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II visited the memorial at Jallianwala Bagh in 1997 and then Prime Minister David Cameron visited in 2013 describing the massacre as “deeply shameful”.

Successive governments have failed to properly acknowledge the scale of loss and trauma of the events that took place on 13th April 1919 and there are people all over the world who are asking the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom to make an official apology for the massacre.

It is soon the anniversary of this abhorrent event and in view of the fact that you are vising India shortly, we feel this would be very appropriate in giving proper closure to those affected across the world.

A proper apology would, to a certain extent, be accepting our historic mistake of a merciless killing of innocent Indians at the hands of the British. This will hopefully enable us to properly develop British-Indo relationships.

We would kindly ask you to consider issuing the apology in the House of Commons and such an action would be greatly appreciated by many.

Kind regards,

Your Sincerely,

The Lord Sheikh